Chronograf: It's About Time

The story of how I substantially reworked the Chronograf.

Two years ago, I wrote about the Chronograf. Back then, I considered Chronograf ‘complete’, and that we just needed to make a production prototype (ie a PCB) to confirm that it worked.

For one reason or another, that never happened.

This summer, I was back living with my Father to work on a project or two before moving on. He mentioned that he was thinking on getting the Chronograf PCBs developed finally - we never drew up a schematic at the time as it was a rolling development, so it’d be easier to do if I was here, as I could look up the pinout for the PIC, the prototype board we had made, as well as check the order of things like the LFO waveforms.

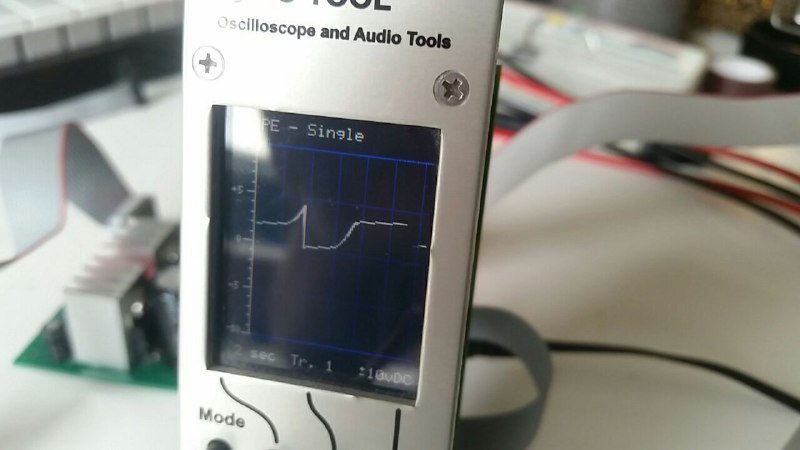

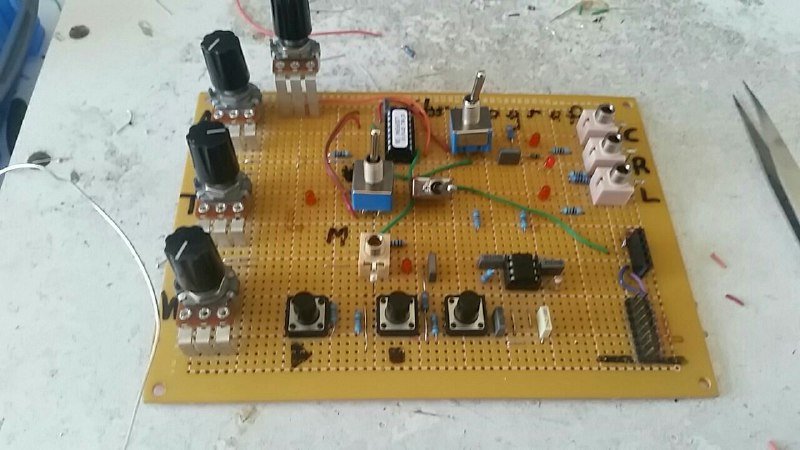

Chronograf’s perf board prototype

Chronograf’s perf board prototype

I believe that we had never particularly even listened to the LFO output of the Chronograf, merely confirmed the waveforms looked correct on the Oscilloscope, as when we listened to the audio on the studio monitors, a distinct high frequency bleeping was audible. We believed that this may be down to the filter used to convert the PIC’s PWM output to an analogue voltage, though after about a week I realised I had a single instruction in my code causing it.

Improving Basic Functionality

Testing like this also revealed a few more issues relating to the exact shape of the Sine wave, and how the PIC responded to a change in Tempo.

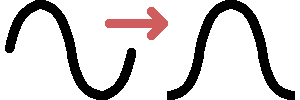

When I had designed the Sine wave, I had done it in the true Mathematics sense, ie starting at the midpoint, then rising, then falling, then rising again. However, the fact that (in the version of the Chronograf at the time) the LFO idled at -5V, this meant there was a audible ‘boom’ as the speaker instantaneously moved from the lower position to the center position. It would be more musical to shift the sine wave 90 degrees forward, so that it started at the lowest point.

Graphical representation of the Sine change

Graphical representation of the Sine change

The Tempo only changed at the end of an LFO cycle. Considering that the Chronograf’s slowest tempo has a period of around 8 seconds, and that an LFO can have a Multiplier of up to 256, this meant that in the worst case, you’d have to wait >2000 seconds (30 minutes!) to respond to a change, which really wouldn’t be good!

My first attempt to fix this was to restart immediately on a Tempo change, however this really didn’t work, as it lead to a chainsaw-like ‘ripping’ effect as you changed it.

I then changed my approach, and created an algorithm that would figure out what percentage of the way through the LFO cycle we were, and then change the Tempo to be that percentage of the way through the LFO at the new speed. Sounds simple, but writing in assembly with only 8-bit integer values, this was a challenge!

The cool thing about this was that you could create ‘kinks’ in the LFO, and kinda sculpt even a boring sawtooth into interesting sounds (and shapes). This would be especially interesting if the LFO was voltage controlled!

(We also briefly experimented with adding a switch to allow the user to select this new mode or the original mode, but we always ended up feeling like we’d prefer to be in the new mode, so we dropped it.)

Creating New Functionality

I demonstrated my changes to my Father using pictures and video clips whilst he returned from his Holiday, and he was very happy. He had been thinking about the Chronograf, and expressed that it’d be great if the Chronograf had a few more waveforms.

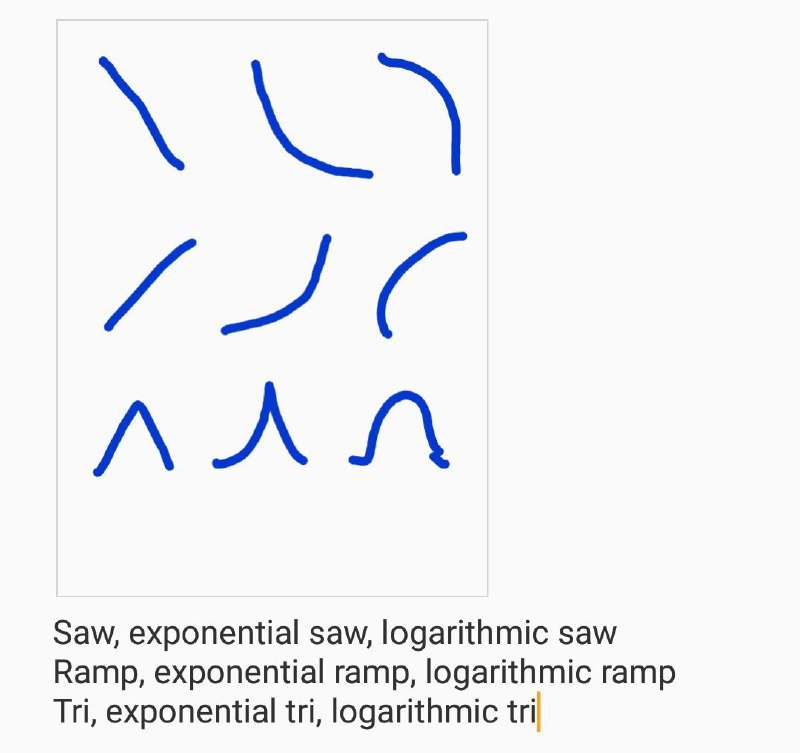

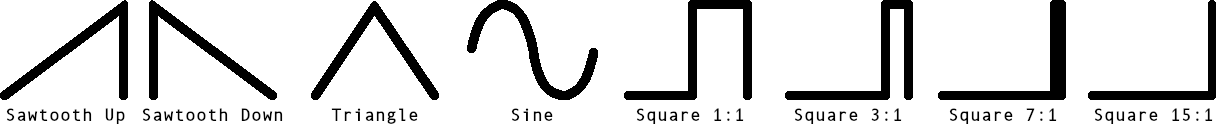

Chronograf’s original 8 waveforms

Chronograf’s original 8 waveforms

The LFO and it’s waveforms has always been less of a focus - Chronograf was intended to be a simple startable/stoppable clock source to control modules like Polygraf. Adding more exotic sounds would give it more widespread appeal.

He expressed frustration that he couldn’t draw using Telegram (the messenger program we use), and I joked that he could draw on his arm and take a photo. He downloaded an app that allowed him to draw and sent me pictures of some crudely drawn shapes. He then also described a toggle-able ‘One Shot’ mode that ‘would just allow one cycle then stop. Which in conjunction with these new waveforms would make it a simple but versatile envelope generator.’

The left column represented waves we already had, and the others represented new waves.

I thought the waveforms were interesting, but was hesitant - every non-linear (curvy) shape requires a lookup table, that says what level to be at for each step. Each value is a byte, and you need a byte for every step. Chronograf allows for 256 steps, meaning 256 bytes per shape, plus a few more to allow the instructions to select the correct ones. We had 546 bytes remaining of the 2048-byte chip we were using, so things would be tight, especially if one-shot mode turned out to be even moderately expensive to implement.

I saw that we could use just one lookup table to create each of saw up, saw down, and triangle, just by reading it in different ways, but it wasn’t until my Father pointed out that Logarithms and Exponents are connected that I realised I could use just one lookup table to get all 6 shapes, by inverting the exponential values (ie 255-x) to create the logarithmic values.

I had programmed Chronograf in such a way that throwing in these new waveforms was as simple as generating the lookup table (again, using SPREADSHEETS!!), and writing a few lines of control code; as such, by the time my Father returned home (5 hours after suggesting the waveforms), I was already able to demonstrate them.

I found that with the 6 additional waveforms, it was hard to get the correct precision on the potentiometer to select the waveform I wanted, which was unfortunate. It’s easiest to allow selection with power of two number of choices (ie 2 choices, 4 choices, 8 choices, 16 choices, etc). We had 14 waveforms, which allowed us to have an additional 2 waveforms.

The Turning Point

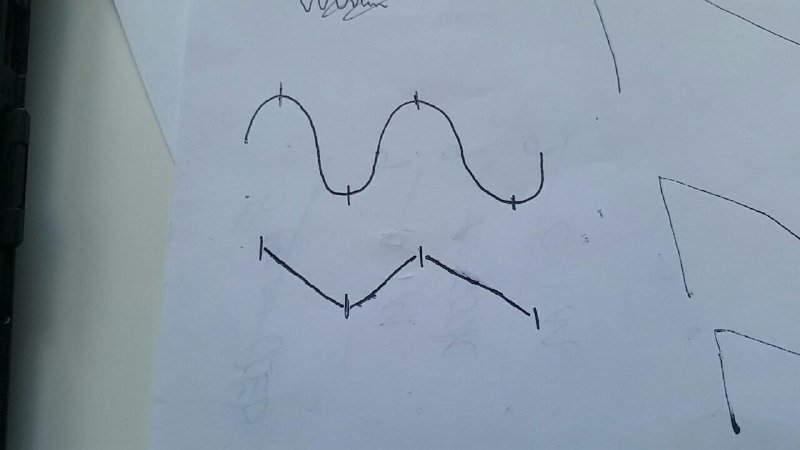

After several days of discussing potential waveforms, we realised that most ‘shapes’ fundamentally were combinations of ‘ups’, ‘downs’, ‘flats’, or ‘stables’, where the ‘ups’ and ‘downs’ can have curves. Triangle is ‘up-down’, Squarewave is ‘stable-flat-stable-flat’, Ramps are ‘up-flat’ Even the Sine wave has curved ‘up’ and ‘down’ components. We could introduce shapes that are combinations of those components, and then augment the ‘ups’ and ‘downs’ to follow a different function for the slope.

Sine is formed from up and down segments

Sine is formed from up and down segments

At this time, we had 4 different functions (linear, exponential, sine, and logarithmic) and 4 wave shapes (up, down, up-down, and down-up).

We wanted to add back in the Squarewaves, as they are relatively inexpensive as they don’t require a lookup table. They’re also particularly useful with Polygraf, as a 3-off-1-on square with a Multiplier of 64 used as an input for Polygraf’s pattern causes it to play a different pattern for every 4th bar (for example).

Having the function parameter allowed us to add four more divisions than our Squarewaves originally had. We also decided that we would add a Pulses mode, which produced pulses in a continuous spectrum from 1-step-on-out-of-256 for 0V on the Function input, to always-on at 5V. This meant that voltage control of the Function would allow for pulse width modulation.

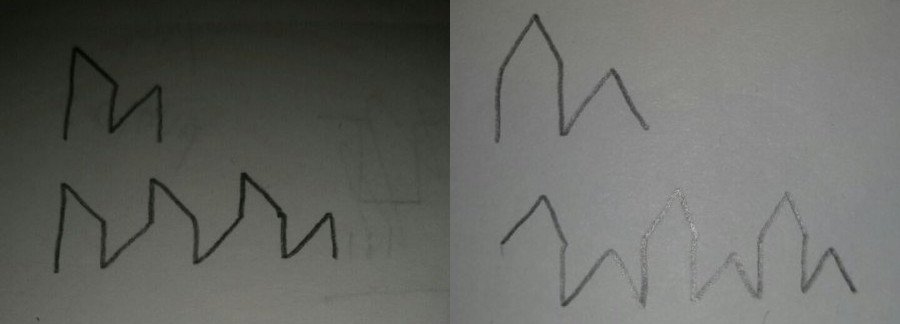

Two rejected wave shapes - Chainsawtooth and Staggered Triangles

Two rejected wave shapes - Chainsawtooth and Staggered Triangles

We experimented with different combinations of ups, downs, and flats to produce interesting wave shapes. We settled on an ADSR-type shape, which has ‘up-down-stable-down’, and an MW-shaped shape, which has ‘up-down-up-down-down-up-down-up’.

We also wanted to cram more wave functions in, to make the sounds more exciting. In particular, we found the shape of the tangent math function and the shape of a decaying sine wave interesting.

Technical Challenge

Adding more wave functions posed a big technical challenge - we didn’t even have free bytes for another full lookup table. I wasn’t content with this answer, and came up with creative ways that gave us more free bytes.

Not enough program memory

In a lookup table, sometimes we have many consecutive identical values in a row (think of the ‘flat part’ of the exponential function). These repeated values can be replaced with an inexpensive 4-byte code snippet similar to if between step x and y, return value z - for some low data-entropy lookup tables, this freed huge numbers of bytes - in one case, I was able to reduce a lookup table from 256 bytes to 25 bytes, without sacrificing resolution. I also realised that I was able to store another whole lookup table in the chip’s EEPROM data storage, rather than program memory.

We can also get a couple dozen more bytes from storing only one quadrant of the sine wave, and half of the tangent wave, and performing math to calculate the rest. This ‘solution’ also caused more problems.

Call stack overflow

I ended up getting a call stack overflow. The 16f684 is over a decade and a half old, and it only has 8 call stack levels. This means you can only have 8 nested call-return routines before you have unpredictable results. Worse still, interrupt routines cost an additional call and add on to call stack already.

If you’re not technical, that may not make much sense, so here’s an analogy. If I ask you a question, but you can’t answer my question until you ask a friend a question, and your friend can’t answer until she asks her friend a question, etc, if this happens too many times in a row, the chain is going to have trouble getting the answer back to the original person. This is made worse if you interrupt someone part-way down the chain and ask a different question, which requires another chain to answer.

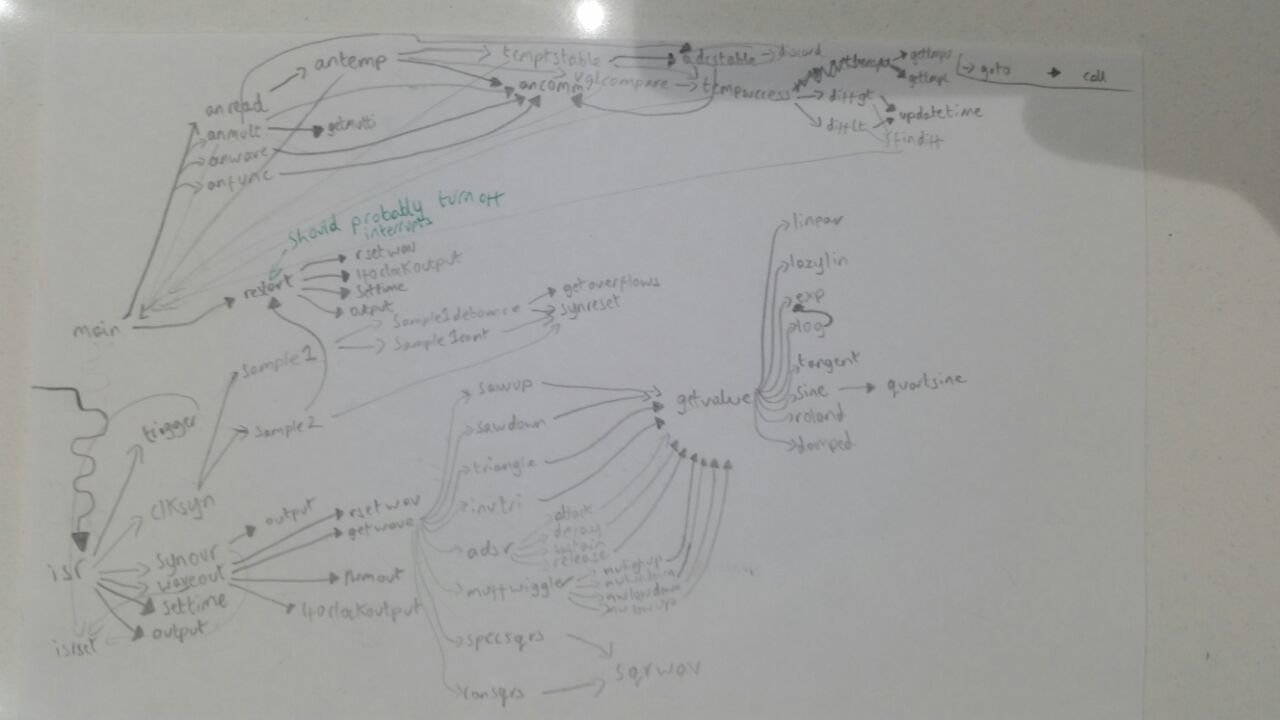

To solve the problem, I went through my entire code and created a graph of every goto and call. It took a while to do, but it helped me identify places with call-returns that could be replaced with simple jumps.

Call stack overflow is a pretty insidious problem, as it may seem that you have solved it by making some change and seeing if everything works. In reality, in ‘just the right circumstances’, everything can and will break again. In my case, I found a point in my code where I had tried to be smart about the fact that a call-return takes 4 instruction cycles to create a very space-efficient 20-instruction-cycles delay routine. If my code had an interrupt occur during this tiny space of time (2.5 microseconds), then the whole program would have stopped working until it was reset.

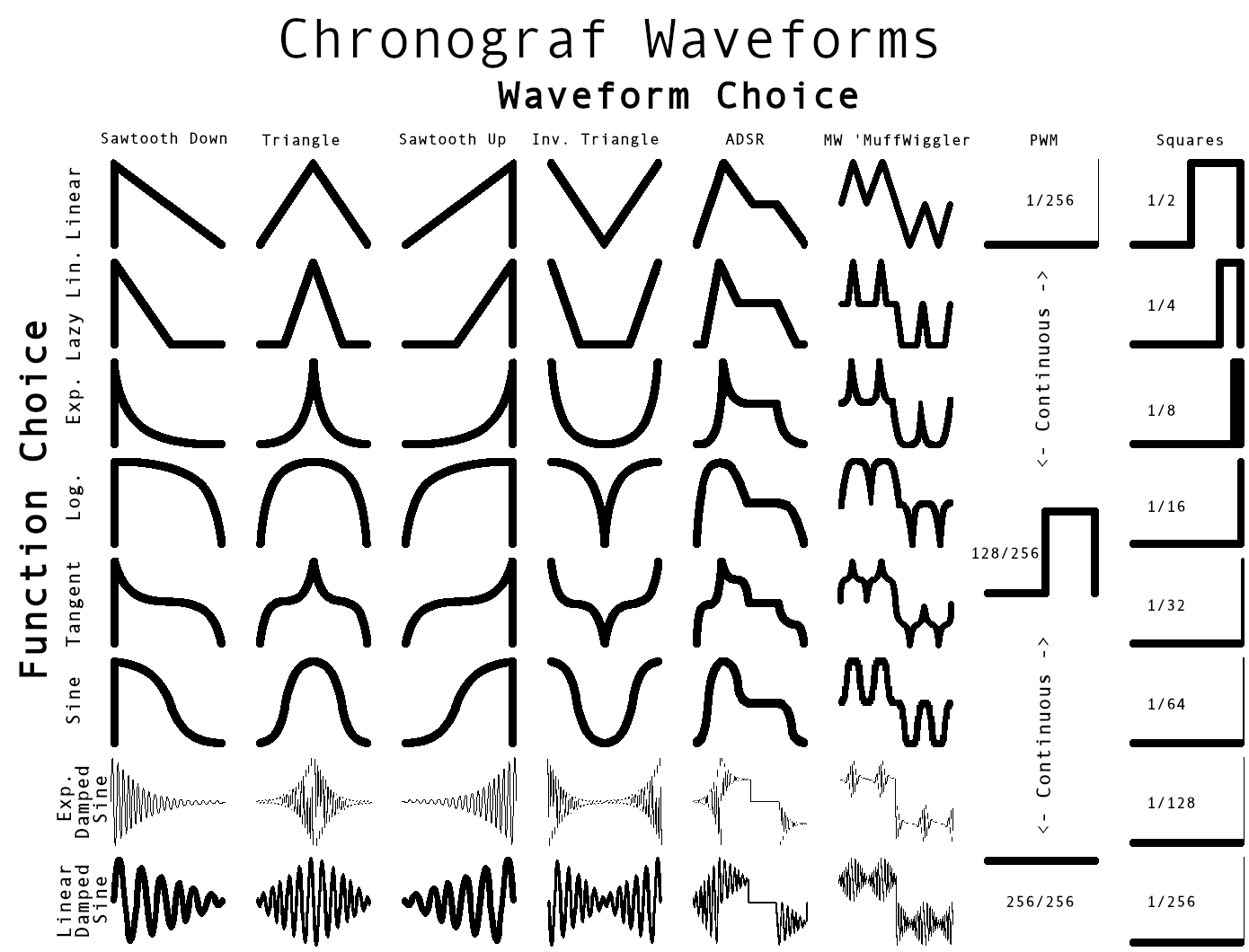

Chronograf’s new set of waveforms

Chronograf’s new set of waveforms

After solving my technical problems, I had a version of the Chronograf with a huge number of distinct one shot sounds! We went from 8 sounds to 56, (or many more or slightly less, depending on what you count), which in my opinion is a huge amount of versatility. This versatility is increased further when you add the fact that you can get the inverted output of any wave through a simple inverting amplifier, producing even more potential sounds!

Demo

We’ve had the PCBs for both Chronograf and Polygraf designed and tested, and they both work great!

I recorded a demo showing the kind of things they can do together. Unfortunately, I didn’t think to not record this in portrait mode, sorry!

Reflection

I had never been that attached to Chronograf when I first made it. It always felt like a knock-off of Tom Wiltshire’s Tap Tempo code (even though they were designed from different starting points and merely reached a comparable functionality). After I learned of Tap Tempo’s features and functionality, it seemed like it would have been more logical to simply ask Tom to implement the start and stop functionality (the only thing that made Chronograf particularly unique at the time) rather than have me start from scratch, especially given that Frequency Central already sports a proprietary version of the Tap Tempo code in Waverunner.

However, since we made the changes, in particular adding One-Shot mode, and the huge expanded range of waveforms, I truly feel like Chronograf has many things to offer that make it a desirable alternative to Waverunner, and I’m extremely proud of it and am excited by it.

It feels like a really versatile module to me; it can be used as a clock source, it can be used as an exciting, quirky LFO, it can be used for Pulse Width Modulation, it can produce simple but versatile envelopes, and it can be started and stopped for use with a sequencer or drum grid. Chronograf packs a lot of power into a little space, and I’m really proud of that.

Chronograf was released (along with Polygraf, Cryptograf, and Seismograf (both versions)) when we launched the new Frequency Central website in mid-November, 2019. Pre-release feedback from Sunshine Jones (who ordered one in advanced of the official release) was extremely positive, so hopefully everyone else enjoys it too.

P.S. I'm late to the party, but I recently got a twitter account that you can follow here.